Anyone can take a photograph, adding to the endless collection of billions of shots online. We need something to set ourselves apart from the ocean of competition, or rather repetition, of the same old images everyone else is taking. The easiest, or even maybe the toughest, method of setting ourselves apart from the plethora of images we encounter is to develop a style that others can visually identify as your style and hopefully even recognize and pick out your unlabeled pictures. When you discover your style, chances are that others will start recognizing your work just by your unique style.

We see a lot of photographs almost every day. They are in ads, social media, products on shelves, commercials, and so many other places. We have a tendency of becoming desensitized to the photographs we constantly see, oft because they start to look the same after awhile. Go online, say Facebook, and you will encounter many, many images per minute, and even more with every click of the mouse. We see sooo many images that we actually tune them out subconsciously…all the way up to the moment we see something amazing or clearly unique, at least to our collective mental database of photographs.

How do we set ourselves, or more importantly our images, apart from the others? By developing a style, something unique about our images. Style can come in so many ways that it can become a science and/or art itself while creating a style. Creating and developing a unique, or unique enough, style not only tends to create stronger images, it can also set you apart from your peers and competition.

A style can be any number of elements in a photograph that come together to create a specific ‘feel’ or ‘look’ that can be identified or recognized allowing someone the ability to guess or identify the person who took the shot. These elements can be any combination of things ranging from exposure, depth of field, emotion, textures, perspectives, colours, juxtaposition, and so on.

So how do we develop a unique style? Well, the word unique is a little ambiguous and maybe misleading in regards to developing a style. The truth is that anything you discover while trying to create a unique look and feel to an image has probably already been discovered, done, and maybe even taught somewhere, possibly many times. Does this mean creating a unique style is impossible? Definitely not! But it can often take a lot of work and maybe tens of thousands of shutter snaps.

One of the easiest methods of developing a style is to look at other’s styles and trying to recreate them. The mere act of trying to recreate a look or feel to an image will take you on a creative journey of discovery, every rejected attempt delivering yet another powerful learning lesson. This isn’t necessarily theft though, your goal being to develop your own style, which can be as easy as combining multiple elements from other’s styles. The point is to start combining visually identifiable elements and techniques so that when a person familiar with your body of work views an image without knowledge of who made it, they are able to guess who likely made the image (assuming they are already familiar with your existing works). Think about Picaso for a moment. Most people can be shown just three or four of his works and then successfully walk through an art gallery and identify many of his works just by noticing similarities in his style of painting, even pieces made many years apart. That’s where you want to be.

When do we know we’ve succeeded in making our own style? Well, when people start looking at photographs and start stating that they think specific images are yours. Once people can tell your images from your peer’s or even competition’s shots, you know you are either ‘there’ or well on your way to accomplishing an admirable and powerful goal. Once you establish a ‘clear’ style, which is rather often ‘unclear’ to verbally explain to another without first exhibiting several examples of your style, you will not only increase the ability for people to identify your images, an amazing and humbling phenomena will likely begin through other photographers starting to either emulate or borrow elements from your photograph style. This is the place to be…others imitating ‘your’ work(s). There aren’t many complements more fulfilling than those from your peers, especially when one asks you if that was your image, when it was in fact yours…or maybe even another’s image that was attempting to emulate yours. But don’t kid yourself, it’s a long and arduous journey to create and establish a seemingly ‘unique’ style all-together yours, but it’s more than worth the time and effort to try.

So…take that leap to create a unique and identifiable style that will stand out from the massive plethora of images we encounter everyday, or rather, from the specific genre and type of photography you feel passionate about. Develop your own style through learning, trial and error, and don’t be afraid to learn from other’s works. And never give up working on that elusive and hopefully easily recognizable style, the end results are often worth more than any monetary compensation via praise, recognition and/or emulation.

So go out in style, or maybe in with style, or even going with a style, just make a style and stick with it, lol.

—

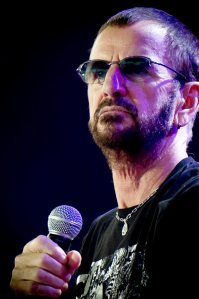

My preferred style of concert photography is a dark dead-space with slightly over-lit, gritty skin tones as seen in this pic of Kelly Gray.

Here’s another example of a favourite image I shot of Geoff Tate from Queensryche.

Concerts are one of the most complicated environs to shoot in, but when the lights are right, the play of dark, light and various colours can deliver images with great impact as seen in this image of Tim Lindsey, the bassist of Molly Hatchet.

My good friend Ken Titus of Southern Xposures loves a slight HDR look to his images, a style I like but definitely distinctive with its pop.

Another image by Ken Titus, this one being an intentional low-key shot taken during a break in the show.

You must be logged in to post a comment.