I believe there are only three aspects to photography, which when mastered collectively, the beginner and/or average photographer can graduate to some varying level of good to great. Although there are any number of divisions of subjects, most, if not all, can be clearly placed in one of the three primary categories, and sometimes, maybe more than one.

The three categories are Technology, Exposure, and Composition. While Exposure and Composition are the meat and bread of photography, and are often enough to take great shots, the understanding of the Technology you are holding all too often makes the final difference when combining all three.

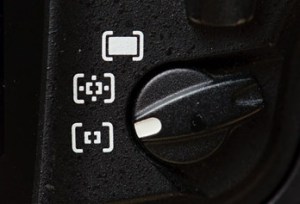

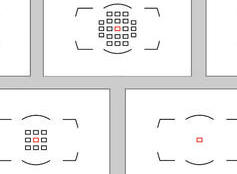

Technology is understanding the limits of your gear. It’s knowing the max aperture and understanding it, how good your camera is at any given ISO, size of images and their applicable resolution to usable screen and/or prints, how lenses compress or distort, battery performance, accessories that actually give you a return on investment, and so, so much more.

Exposure is creating correctly lit subjects and scenes. It’s understanding how the physical components of Technology in regards to Shutter/Aperture/ISO work together in order to see, not see, emphasize or demote elements within the frame, and balancing the overall image in order to make a usable and hopefully aesthetic image.

Composition is creating a compelling image at some level and/or to some audience. It’s knowing how to place elements within a greater picture, showing or not showing something to give you some message or feeling, targeting your audience, and telling ‘a’ or ‘your’ story.

Exposure and Composition are often seen or used in tandem for/in many aspects, but understanding how each works independently is critical along with how the technology of the given camera being used affects the ability of composition and exposure.

Too many people tend to go out purchase an all-in-one book hoping to learn everything by the end of the book. Well, it’s a beautiful idea but usually a monetary and educational loss in the end. Most beginner/amateur photographers I have run across have at least one to three, often more, of these books taking up both valuable shelf space and cash investment. At an average of $50 a piece, these all-in-one books are a costly shelf anchor after you realize that you became a victim to statistics and never got past chapter 1, 2 or maybe even 3 (congrats to you if that’s you). This is the second most costly mistake for photographers, usually right behind buying a bunch of accessories and/or lenses that you either didn’t need or have no clue how to use to the full monetary value of each item. The greatest mistake usually being purchasing those more expensive lenses or even a ‘better’ DSLR thinking that will improve your photographs, but again, is a failure if you don’t know how to squeeze the most out of those specific features that drove up the price of that item. E.g. if you purchase a 50mm f/1.4 prime lens for $500 instead of a 50mm prime lens f/1.8 for $200, AND you don’t consistently shoot at f/1.4, well…the math is obviously $300.00 USD!!! That $300.00 of other accessories or books you could have purchased at a much greater potential return on investment.

My suggestion to the above point(s) is to first learn how to use what you have on a hardware level (the DSLR and lenses you ALREADY own) starting with the camera manual or one of the nice color third party replacement manuals, purchase a book on composition and a book on exposure with ratings of four or five stars on Amazon that have ‘less’ than 200 pages or even 150 pages. These shorter books are easier to finish and have a distinct advantage of concentrating on one meta-subject instead of 30-50 attempts to make unique subject chapters in the all-in-one books. I myself probably have $500 in print all-in-one’s and another $2,000+ in digital versions, and I’ve never finished a single one! I also have at least 100+ hard copies of specific/specialty ‘subject’ books and another 300 or so digital versions, and I’ve probably read a quarter of them all and quite often multiple individual chapters in each, using the vast library as a reference collection. In other words, I’d rather buy a $30-$40 specialty subject book and read 25-100 pages in each than to purchase a $50-$75 all-in-one and only read the first 20 pages and get bored before chapter two tries to explain electronics and the difference between a photo-receptor and a pixel, much less how the Bayer system works (which by the way, I personally like, BUT, it has no real value to your being a better photographer).

So there you are. Buy a book on composition first, that you can finish, then purchase a book on exposure, that you can finish, and then go and read a better manual on your camera to figure out what and how to use all those cool features that you need to know in order to get off and away from all those auto modes that horrifically constrict you in certain situations. Although there are places and times for auto modes, I use them on occasion myself, the true control and full potentiality of your photographic skills usually comes from shooting in complete manual mode (minus the few auto settings in-camera, NOT Aperture/Shutter/ISO). Master Composition first, then Exposure next, and finally the Technology in your hands, and you will propel yourself years, and sometimes decades, ahead of your peers with same exact equipment in hand.

You must be logged in to post a comment.